A Few Words On The Honorable Acceptance of Wisdom

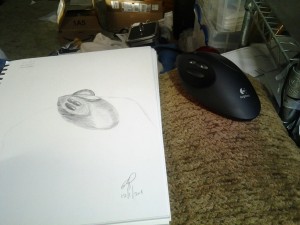

I did a sketch last night, the first after the lesson I got at the Allentown Comic Con, and it turned out fairly good, I think. But I also got an email from a writing group I used to belong to, and it got me thinking about the nature of criticism, and how two very different styles of critique affected me.

I’d like to compare and contrast, for a moment, two diametrically opposed experiences. Each involves being given criticism of my work by a professional — someone who has sold significant volumes in the profession — by my own request. Neither of them just walked up to me out of nowhere and started giving me advice, I asked them for it, and they gave it to me.

First off, I consider it very valuable and considerate of any pro to take a portion of their time, which represents a salable commodity, to teach me anything. I do appreciate it. They’re sacrificing time they could be using to create something to make themselves some money in order to give me advice. That’s very kind of them, and I recognize that for what it is.

I’m going to leave out names, because while one of these is complimentary, the other, unfortunately, is not, and I don’t want to identify that person lest he feel embarrassed. It’s not my intention to do that, it’s my intention to make a very general statement on the subject of critique, and why we do it in the first place. It would just be mean to poke at this person by name, so I’m not going to do that. You’ll probably know who the positive one is anyway, but that’s ok, I don’t mind if the positive one is identified, that shouldn’t cause any harm. That said, here’s the comparison:

I once belonged to a writers’ group with a number of members that got together every couple of months to read over short stories or novel excerpts and offer critiques of each others’ work. The process was fairly simple: A couple of weeks before the gathering, send a PDF of what you want critiqued to a central email address, and it would be distributed so everyone attending would have an opportunity to read it. Copies would be provided at the session, but reading it ahead of time was a good idea. Then we’d all show up at the designated member’s house, have some takeout food, and sit around and go round-robin style, taking turns giving our impressions of the work. It was generally very useful, with lots of good input, catching plot and character flaws, pacing problems, and stuff that just doesn’t work. Note the operative word — “generally”.

There was one member of the group, a published author of some local note (I never read any of his work), who seemed to derive a great deal of pleasure from being the group’s own little Simon Cowell. He didn’t seem to have the words “constructive criticism” in his vocabulary. He would let seven, eight people tell you “I like this, your characters are well-made and solid, I identify with them, the plot moves right along, you only have this little difficulty with this image of the tree…it just doesn’t seem to fit here, can you refine it?”, then wades in with something like “This was just awful. Frankly, I don’t know why you bother. If it were mine, I’d trim it down to a hundred words and make a Feghoot of it, or better yet, just stick it in a drawer and forget about it.”

This is typical of his sort of criticism. Not how to improve the work, but just tearing the creator down and belittling them. I tried going to this group many times, one stretch of about a year, the second about seven months, but this person’s continuous toxicity made the experience so painful I eventually stopped going entirely.

Compare this to the more recent event, where I received a critique of a quick sketch by a pro comic artist, who, rather than immediately saying “dear God, that looks like crap!” — which, honestly, would have been accurate —

he said “I didn’t know my head was that round…but you did capture my energy. Let me get a pencil, and I’ll show you a few techniques.” He then spent half an hour — occasionally looking over at his table to see if he had a customer — to basically teach me how to draw. He suggested books for me to read, and we parted with me effusively grateful. Even though he still essentially thought my original sketch wasn’t very good. It was the same assessment of the work — but a radically different response. I was glad for this response. It left me better off than when I started.

I have a fairly thick skin when it comes to insults, and I know how to accept criticism graciously, but there’s an unsubtle line between criticism and abuse, between teaching and tormenting. A teacher encourages you to join them up where they are — a tormentor wants you to stay down below, so they can continue to step on you. The same exact input can be treated with two diametrically opposing methods, one resulting in discouragement, the other in resolve.

When I did the sketch above, I didn’t really know what to draw at first. I didn’t feel up to a life drawing yet, but didn’t want to draw fruit. So I looked around, and the trackball was handy. It had interesting curves and shadows. So I tried it, and it came out pretty good. I surprised myself. For the first time, I think I can really do this.

Nice sketch of the trackball. I just recently started taking an art class and am learning to draw. After a few lessons, I drew a sketch of a baseball, and had a very similar reaction to yours. “Wow, that’s not bad. I think I can actually draw. Now my teacher has me working on a kind of a surreal drawing involving a monkey. I’ll share it with you when I’m done.